Reflections On Trauma and Recovery

I

The day it happened, I was feeling incredible.

The sun was shining brightly, it was my second day back home in Bermuda. I’d just escaped a frozen and locked-down Montreal Covid winter, uniquely bleak beyond the standard-issue seasonal depression. My left elbow, surgically reconstructed a year ago, was finally moving normally and without pain. I felt free, euphoric, as I reconnected with my home island that I’d been distant from for several years, swimming, diving, scrambling around rocks.

There was a jump that had been in the back of my mind for a while, one of several well-known ‘gaps’ in Bermuda. Spots where you take off from far back from the edge of the cliff and need to fly over several meters of rock before clearing the cliff edge and heading towards the ocean. As a teenager, I’d checked off three of the four most notorious jumps on the island, and I woke up that morning on a mission to clear the final spot; a nod to my teenage efforts and the things my friends and I did to chase sensations of aliveness and purpose while growing up on a remote sliver of island out in the Atlantic.

It was windy, the water below chopped and swelled. I paced the lower shelf of rock I would need to clear, measuring it to compare to jumps I had made before. I stepped through the run up several times. I had about four steps, barefoot on sharp rock, to build momentum into the takeoff. Any stumble or misstep once I’d committed would be really bad. I took my time measuring and rehearsing the process.

The jagged edge of the cliff I would need to clear disappeared from view as I backed up to the start of the run up. Last little mental checks. Jump high, jump out. Hips need to drive upwards first and then slowly rotate into the dive; if I dove straight forwards I wouldn’t make it. Familiar butterflies radiated from the pit of my stomach to my throat, my life-long unease around heights making its presence known. I had come to love those sensations, intense fear that made me feel alive and spring-loaded the rush of success that hopefully awaited.

The run-up was perfect, I accelerated rapidly and channeled all of my adrenaline into my right leg that launched me upwards and outwards. The rocks over the lower ledge flashed into view below as I cleared them with ease. A split-second of intense relief as ocean filled my vision.

Then impact. The sprint and power of the jump meant more momentum and air time than I anticipated. The laser focus on clearing the rocks meant little thought put into how I would hit the water. I landed vertically, pencil straight. The familiar shock of cold water to the nervous system was followed milliseconds later by a brand new sensation as the top of my head thudded into the ocean floor.

Disbelief. A lightning bolt of compression sped through my spine. I surfaced. Everything was blurry, my vision was registering everything as tripled for a few moments before recalibrating. I stayed conscious.

The water I landed in could not have been more than seven feet deep, lower than I’d experienced it before in that spot but absolutely not out of the question for how dynamic tides and surf levels can be in that spot. I neglected the depth check that needed to have been done, and the worst case scenario had happened.

I pulled myself onto a close by rock to assess what had happened. My arms and legs could still move. I was still conscious. There was sharp pain in the base of my neck, a sensation of compression that was felt both dull/thick and urgently stabbing at the same time. The waves were loud and washing over the bit of rock I was draped on, a rising tide that felt urgent. I weighed my options, and soon slid off into the water and swam stiffly and urgently, relying heavily on my legs, until my feet touched sand and I could walk in the rest of the way.

December 14, 2020

I was initially treated with a surprising lack of concern as I walked alone into an overcrowded, understaffed Covid-striken hospital (I was alone the entirety of my hospital stays throughout this experience, no parents, no visitors, nothing due to Covid). No brace was put on me, and I sat stiffly in a normal chair waiting for my X-ray, and was then escorted to a vacant gurney at the end of a hallway and left to wait as no beds or rooms were available.

The dreamlike sensation of shock and confusion that had been with me since the impact persisted.

A doctor arrived a few minutes later and sat down next to my stretcher, looking pale and at a loss for words.

‘I can’t believe it,’ she said. ‘I can’t believe it. Your neck is broken in two places. Oh my god. My boys jump off those cliffs all the time. I can’t believe it.’ That was all the information I got as a flurry of nurses descended on me, clamping on a brace, inserting an IV, and rushing me down the hall towards the MRI room.

The dreamlike state was shattered by a rush of panic. Rapidly escalating spirals of terror swirling into the abyss opening up in the pit of my stomach. ‘You need to take me out, I’m going to die.’ I remember saying loudly, over the whirring of the MRI machine. Panic attacks feel like that.

Then, another blur of nurses, movement, bright lights, and I found myself in a room, still on the same stretcher. A minute or two later a different doctor rushed in, an older man. ‘Why’d you do that!?’ he yelled.

‘Why did you jump!? Why’d you do that!?’ he yelled again, embodying a shocking amount of ‘confusion projected as anger’ energy that hit on some buried trauma. I don’t remember understanding much of anything else he said, before he stormed out as the second panic attack hit.

Uncontrollable shaking, sobbing, panicked confusion, and a deep sense of aloneness as once again the pit opened up and I swirled into it. A nurse whose name I never got took my hand and stayed with through the duration, speaking softly and telling me things were going to be okay.

Then some morphine. The edges of the pain blurred and softened. Gently euphoric calm to the head that smoothed over the urgency of the panic and faded it into the background. My breathing settled. The first doctor returned, more calm, and talked me through the situation.

My C6 and C7 vertebrae were broken. They were going to keep me in the hospital for a couple days. They would know more tomorrow about the next steps. In the next few hours a room would open up and I would finally be transferred from the stretcher to an actual hospital bed. No visitors. Half an hour later a bag was delivered to me from my parents containing my laptop and a couple books. A couple hours later I was finally moved to an actual bed.

The angry doctor came back the next day, still needlessly hostile. He gave the initial diagnosis - multiple fractures to the two vertebrae. But stable. Meaning as much immobilization and bed rest as possible for the next 6-8 weeks while my body healed.

I was asking questions about what my next few days and weeks would look like. Could I take my neck brace off and shower?

‘Yeah is that what you want to do?? Go home and take your brace off and be stupid and get paralyzed?’

December 18, 2020

A day later I was sent on my way, with a hefty collection of pain meds and an appointment to return in a week for more imaging. The first days passed in an opiate haze, laying mostly motionless in a hospital bed that had been set up in the guest room of my parent’s house. I researched whatever I could read about broken necks and recovery, trying to keep the anxious thoughts at bay and attach myself to an optimistic narrative. Okay good, there’s a rugby player in Scotland who had a similar injury and she’s playing rugby again now. Oh shit here’s an article with some grim statistics about chronic pain after neck trauma. Okay good here’s another inspirational story. Oh shit this mountain biker died.

About a week in, I could sense that the pain was worsening, and sharply.

I didn’t really know how broken necks are supposed to feel. But this didn’t feel right. My neck hurt, obviously. The inside of my shoulder blade hurt even more. Pain was stabbing and shooting its way around, even when I was completely motionless.

This was my first introduction to a special sort of dark place that I’ve revisited often throughout this process: the sensation of lying in bed at night, motionless, neck fully immobilized by a brace, the maximum dose of painkillers and sleep meds I’d been prescribed floating through my system, while my body sends ceaseless waves of urgent pain signals, the kind that activate your whole nervous system.

There’s nothing else to do. There’s no position that could possibly be more comfortable. There’s no more medication to take. My neck, my shoulder blade are searing hot and my brain is on high alert like we’re dealing with an active threat. And it’s 3am and I’m alone.

I went to see a different doctor for a second opinion. More imaging was requested. I got X-rays done on the 24th of December. Then Christmas. Then Boxing Day morning the phone rings and it’s the doctor’s office telling me to come in immediately.

The fractures are not stable.

A loose bone fragment that had been separated from my spine had shifted noticeably in the direction of my spinal cord. Waiting for it to heal on its own is not an option anymore. Nerves are being damaged. And if it gets to my spinal cord it’s over. Change of plans: it’s going to need surgery, urgently, to fuse the broken pieces together so they don’t move.

No one on the island is qualified to do this surgery. I’m going to be connected to someone in Boston and sent out there on the earliest available flight. I ask the doctor for some reassurance about my recovery, sports, and life. He is not pessimistic but he’s choosing his words carefully and speaking in a serious tone. My questions don’t have the answers I’m hoping for. Light-headed again, and the familiar rush of panic.

II

The next day I’m speaking on the phone with my surgeon, Dr Parazin. The first thing he tells me is to go light a candle or whichever ritual I prefer, since nine out of ten accidents like I just described resulted in death or paralysis.

The C6 and C7 are the ‘best’ neck vertebrae to break, he says. C1 and C2 you’re pretty much dead instantly. C3 your breathing probably stops. And no matter which area you break, any type of compromise to your spinal cord is paralysis territory. And these are minute, millimeter differences in a random dice roll of outcomes when you slam headfirst into the ground from 30+ feet. It feels a bit like shooting a pringles can out of a gun at the floor and hoping the right pringles break.

More waiting, the earliest surgery date is in almost two weeks. Paperwork, painkillers, patience. Panic. Some nights the drugs get me where I need to go and I sleep. Most nights I’m in the dark place, pushing down waves of fear and pain that demands attention. Every unintended movement or jolt brings vivid imagery to mind of a loose bone fragment cutting into my spinal cord.

I arrived in Boston and spend a week there counting the days down and going through a litany of surgery prep, appointments, imaging. I’m told I cannot keep the chunk of bone they are removing from my spine, something something ‘federal health protocol’, ‘risk of spreading diseases’.

The nerve pain is brutal at this point. 10/10, around the clock. The pain meds poke around at the edges of it but nothing more. There’s nothing to do but ruminate. I watch a few TV shows but mostly pass the time with my eyes closed and the same playlist on repeat, dissociating as far away as I can.

The day before surgery goes by minute by minute. I flip through a massive binder of information. I take the most stiff, anxious shower of my life to cleanse the back of my neck and whole body as thoroughly as I can with bottles of antibacterial solution I’ve been given. No more food, just weird tasting beverages to get ready for the anesthesia.

My surgery is on January 6th, 2021. Great day all around in the USA. My parents drop me off at the door into a waiting wheelchair (Covid protocols again). Everyone else in the intake room and pretty much the entire hospital is 65+ years old. If you’re young and getting a spinal fusion something has definitely gone wrong somewhere.

Clothes in a bag, hospital gown on, pre-game meetup with the surgeon. He doesn’t know yet if he’s going to need to fuse my C5 in with the other two as well for more stability. He’ll see how it goes. I ask him again if he can just slip me the chunk of bone he’s taking out and no one needs to know anything. He says he’ll see what he can do.

------

Waking up feels like slowly coming back to life. I try to put together what’s happening. Machines are beeping, there’s tubes in my nose, and there’s some type of machinery on the lower half of me massaging circulation into my legs. I can sense a nurse's presence doing something off to the side.

I start to activate my body to shift my eyes in that direction but the first micromillimeter of movement sends this white hot, searing pain shooting through the back of my neck.

Oh right.

This pain is brand new. Oh right. The incision. Five or so inches long and deep. All the way to the bone deep. It’s been glued shut, dressed, and bandaged but the tiniest hint of movement, a twitch of my nose or even a fucking blink and it feels like it’s being ripped open all over again. I speak to the nurse, barely moving my lips. It’s bad. It’s really bad, I say. I can’t even think thoughts without feeling like someone is cutting my neck open with a machete. She comes back and sends a significant amount of oxycodone and probably ketamine through the IV.

I blast off into the stratosphere, floating somewhere I’ve never been before and haven’t been since. Later on or maybe the next day my surgeon comes in. It took a very long time but went as well as it could have, he says. Only needed to fuse the two affected vertebrae. Email him if I have any questions. A fist bump and then he’s off to save someone else’s life.

The incision is a new beast entirely, overriding everything else. I can’t move at all and can’t feel any sense of awareness of what’s happening in the rest of my neck.

A physical therapist comes in at some point with way too much energy. ‘Alright, time to get moving! Gotta get things moving!’

I really can’t, I say. I’ve been lying completely motionless, and if I forget and do something stupid like take a sip of water it feels like someone is pouring liquid fire into my incision.

She doesn’t seem to care. Up we sit. She gets me to gently rotate a few centimeters to the left. Now to the right.

‘Please. I can’t. I can’t move anymore.’ I’ve been in and out of hospitals, physios, and pain management my entire life. I’m proud of the tolerance that’s developed along with me since some of my earliest memories. But in this moment, tears are rolling down my face and I’m begging not to be moved.

She makes me move more. She gets me up out of bed to see if I can walk a bit without assistance. I can’t. She helps me over to a chair on the side of the room, telling me how important it is that I activate even a little bit. Then, she leaves to go deal with other patients, leaving me on this chair. The pain is white hot, blinding me as it stabs at my brain. I feel dizzy. Things start to spin. To my left is the pull cord that activates the nurse intercom. I reach for it.

‘Hey, I think I’m going to pass out.’

My next memory is opening my eyes and seeing the floor directly in front of my face. The first nurses to arrive running had caught me as I’d lost consciousness and lurched towards the ground. More rushed in, and I was lifted by five or six of them and carried back to the bed.

It’s hard to remember much else specific from the stay, everything blurred together. I had books and a laptop but it was too much effort to interact with them. I was rarely fully asleep or fully awake. I remember facetiming friends but little of what was said or exactly who I talked to.

A few days later I was discharged. Another week in Boston, staying at a friend of a friend’s house in a rented hospital bed while my parents took care of me. A week later I was cleared to fly and headed up, alone, back to my apartment in the middle of a frozen Montreal lockdown.

The first two months are hazy and blurred. Music in my ears constantly to escape. Covid lockdown continued, I saw almost no one outside of the people I lived with. The incision took over a month to close, needing constant dressing and attention. I’d often open my eyes in the morning and find myself glued to my pillow in a mess of congealed blood and scab tissue that had formed overnight, a painful mess to rip free from.

I was 25 and this was the first time in my life I had ever had to sit with myself to this depth. Movement was always been the solution for me for the ever-present spectre of existential terror that had haunted me since a child, raised in a restrictive religious environment, my head filled with imagery of hell, evil, and eternal torment. Moving was always the solution. Go play a sport, go learn a new flip, go leap off a cliff, and you’ll be distracted from the weird feelings. Now I couldn’t.

Pain was so normal my entire life. The sensation made me feel alive. I realised I loved it and always had. Risks, recklessness, pushing my limits. Actions that would either bring me the high of success and accomplishment, or the aliveness of pain and overcoming the next traumatic obstacle as a scaffolding of purpose for my life, a source of meaning and a distraction from constantly lurking terror I could never name or understand.

I had long stopped believing in things like a literal hell and had left the church. Intellectually, I could say all the right things about how and why those beliefs didn’t work for me anymore. I built a busy, active life, chasing goals, engaging socially more than I ever had in my life, and constantly living for the future and my goals because that felt normal. So why was the terror still there?

-----

The world thawed by April. I was feeling remarkably better. My brace felt much less necessary, it took fewer meds to stay on top of the pain, the incision was finally closed. My first session outside tossing a frisbee with my roommate felt ecstatic. I ran, I jumped, my legs feeling springy and my upper body moving freely. Incredible. All the injuries I’ve had to that point in my life had been defined by my athletic limitations, what I could and couldn’t do. And here I was, months after the worst thing I had ever experienced, sprinting and leaping around like nothing had happened. Unreal. I had done it.

The first back-track surprised me. It was July and August and much was still difficult. Why were my muscles spasming so much? Why all the headaches? Why could I sprint, jump, and move with the same fluidity I had always had, but couldn’t wear a backpack? Why did I need to rest constantly from exhaustion throughout the day even from simple tasks like sitting at a computer to work or cooking dinner? Why did no pillow I ever tried feel comfortable, why was sleep impossible without pills?

Nine months after surgery, I moved to Spain for a year-long masters program. I’d applied the previous fall, and woken up to a surprise acceptance letter the morning after initially breaking my neck. Moving meant a break-up, a new social circle, and a sped-up pace to life that was unfamiliar after the pandemic years and recovery.

The pain was getting worse with the uptick of activity and stress, I was back to those familiar nights of red alert levels of tension and pain. But I was focused, outputting a high quality of music, and training and competing in sports at a high level, still imagining myself on a linear curve of recovery that would just keep improving.

Then I had my first seizure.

It was late October, my muscle relaxants were running low and I’d been splitting them in half, then quarters. The spasming was getting a lot worse, my jaw stayed clenched, there was pressure in the base of my skull. I stayed up an entire night, working until 8am in a state of stress on a project that I needed to present in my 11am class.

That night I was at a friend’s house watching an episode of squid game that featured an intense scene with lights strobing on and off while people murdered each other. I got up to step on to the porch with a glass of water, feeling mounting pressure in my skull and spasming worse than I’d ever felt before.

Then it started. I collapsed, the glass smashed. I pulsed in and out of consciousness with a terrifyingly precise rhythm. My muscles were out of my control and switching rapidly from complete tension to complete release, while my brain was being switched on and off. Intense lucidity to black nothingness. Pulsing endlessly.

The worst of it lasted around 5-10 minutes, time was difficult to keep track of. I began to feel slightly more control during the ‘lucid’ moments of the pulses, but always flickering back to nothingness in less than a second. I pulled myself across the floor during the moments of control, trying to escape whatever the fuck was happening. The pulsing was relentless. I managed to get a hold of a large water bottle during one of the controlled moments and doused myself in it. The shock of cold water snapped me more towards the ‘controlled’ state, and the flickers to black didn’t go as deeply, more to a blurry, fuzzy, grey.

Reality took a long time to grasp again. The pulses faded slowly over the course of the next 24 hours. The fogginess lasted several weeks. A couple months later, I had another episode, but less intense. Spasming, collapse (conveniently always holding a soon-to-be-smashed glass in my hand as I tried to hydrate away the rising sensations), but lasting less than a minute.

Bermuda, 2025

III

Five years in, the process of acceptance is non-linear and ongoing. A significant step was in December 2023, when it really registered that ‘back to normal’ wasn’t a thing that existed. I hit a rock bottom, pain levels were rivaling what I’d experienced initially and right after surgery. Montreal’s winter was hitting and the cold was an exponential multiplier to the issues I was facing. Any exposure to the cold sped me rapidly from ‘some muscle soreness’ to ‘red alert pain’ levels shockingly fast. Most nights involved the familiar dark place, the experience of laying down in bed, as immobile and comfortable as I could possibly make myself, and flashing red pain alerts firing off in my brain.

A CT scan revealed the osteoarthritis spreading through vertebrae above and below the fusion. Expected, eventually, the doctor said. Not always this advanced this early. But it varies and is hard to predict.

A physio helped make it more palatable. Arthritis is degenerative by nature, but my body’s relationship to it, the way it affects the surrounding muscles and areas, was still something I could control and improve in. It would oscillate throughout my life. Movement is key. Playing sports is key. Warmth, fluidity, motion. It all feels incredible. Sitting around defeated waiting for things to stiffen is never going to be an option.

The fusion itself feels a bit like a black hole. I can’t bring my awareness to the screws in the same way that I can with other elements of my body that are native to it. But it creates a force field of tension, degrading joint rubbing unnaturally, weak and knotted stabilizer muscles that shoots out in every direction. The fused bones are stronger than ever and have been since surgery, locked in place permanently with titanium screws, while the surrounding areas adapt to the effects of the trauma.

Words like ‘recovery’ and the success value I placed on them needed to be understood in a different framework. Surgery is a very sanitized word and procedure. We love quantifying things with numbers: percentages of success, lengths of recovery, etc., all abstracting the visceral realities occurring behind hospital curtains. The actual lived experience is somatic, violent, impossible to properly slot into numbers and data.

There’s a lot of difficult things to sit with in all of this. Unresolved pain, situations that will have ups and downs. Presenting them chronologically here, sequencing memories of things that happened alone, hazy from medications has been an emotional and theraputic experience.

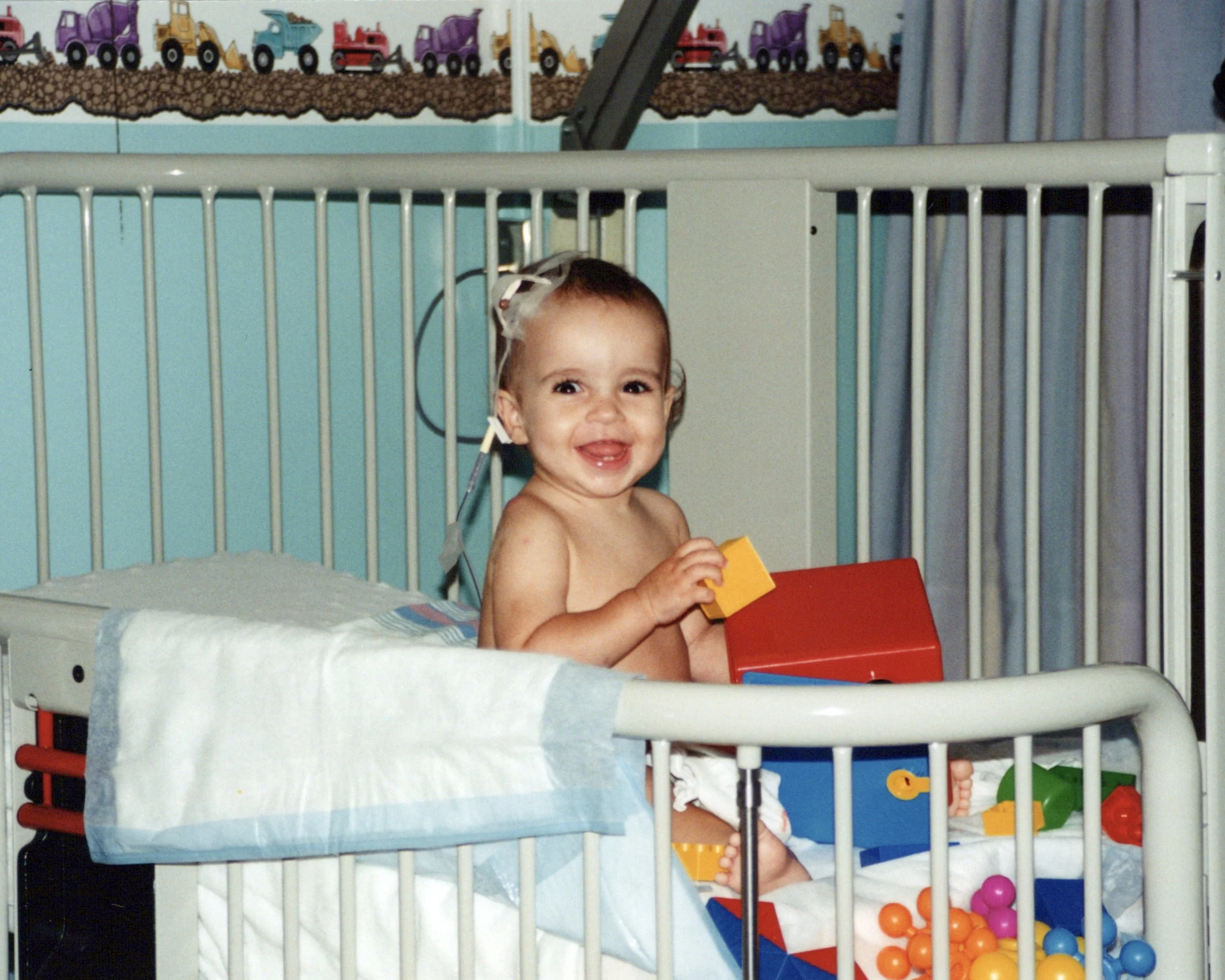

Montreal, 1996

My body remembers things I don’t. When I was a baby, I almost died from an infection. I have an immune disorder that wasn’t known at the time where the mechanism by which my white blood cells deal with infections does not function properly, and within hours a rash had turned into wounds all over my body rapidly eating through flesh. I spent almost two months at the hospital. I don’t have conscious memory of this, just the scars scattered across my body, the stories people told me, and the ongoing experience of managing this disease.

It didn’t click until well into adulthood, processing my neck surgery, just how much the body remembers from traumas that weren’t consciously remembered or stored in the brain’s narrative. I remembered nothing from my infancy and long hospitalisation. Similarly, surgery sends you deep into the realm of the unconscious while trauma your body would not survive without modern medicine is intentionally inflicted to accomplish a greater good. You wake up and things are completely different, your body went through something that changed it forever and none of it was registered in your conscious narrative.

The body remembers, as it constantly runs unconscious tasks, shifts, tenses, and shapes itself around situations.

Awareness has become survival. Mindfulness, yoga, scanning the body as it shifts and responds. Shifts that used to be subtle are now loud. Tensing up a bit from cold, stress, difficult emotions, a negative interaction, has an immediate impact on the knotted mess of tension on the back of my neck. Pain goes from zero to 100 in seconds. The duality I used to unconsciously make between the domains of mind and body, and who is in charge of who, all of it blurs.

I now see how the experience of emotions that I used to define as belonging solely to the domain of my head/narrative/ego have deep roots in the physical make up of the body. The feedback loops between thought, emotion, and physical sensation are instant, the symbiosis undeniable. What it means to be ‘myself’, consciousness, a body, all of it has shifted significantly.

I used to heal my physical problems from the level of the head/ego. My body was my vehicle to take me the places my brain needed to go to check off the goals and narratives it created. Athletic performance, mental toughness, responding to pain by pushing past it, ignoring it. Checklists of accomplishments that would define a successful recovery.

The actual acceptance is letting it be different, letting it be hard, letting my physical limits stop me when they need to even when the mind doesn’t want to accept it. Letting the tears flow, sitting with the pain that won’t be fixed tonight (or probably ever) and allowing it. Finding the space where the self exists that is not the pain, merely experiencing the pain. The pure blue sky of awareness that is always there, beyond the clouds, no matter how stormy or dark the day is.

And the beauty of those shifting definitions, the deeper flows of acceptance and alignment with the body, is in the life that builds around the scars. Not covering over it, not returning to normal. Respecting the often brutal realities and adapting, finding intense meaning and depth in the spaces between the limitations.

-----

Amazing connections have formed. A huge takeaway from the last five years has been a new appreciation for the level of pain so many people carry behind the scenes. Nuanced trauma that doesn’t fit into neat containers or have obvious solutions. The unique life circumstances everyone faces and the shapes they form around their own pain and scars to adapt.

These conversations are life giving. Not because we need to rank and compare our experiences, not because we’re going to fix something by the end of the conversation. Just creating spaces where pain can be acknowledged as it is and sat with together. Never feel shy to reach out.

Lots of love to all who have been there behind the scenes these last five years.